Hydrogen has come a long way, but has further to travel

Hydrogen is the dark horse of the alternative energy field. In the course of a decade that witnessed the steady rise of wind power, tidal power and solarPV, the lighter-than-air gaseous fuel has attracted almost no mainstream press comment. But suddenly, over the past six months, it’s jumping out everywhere – fuelling German trains and Scots ferries, ready for deployment in Beijing taxis, powering forklifts in Amazon delivery centres. How did it remain invisible for so long?

The answer is partly to do with the practicalities of application. The earth lacks any natural reserves of hydrogen, which must be generated from other substances using more energy than that which can be extracted from the gas produced. In other words it’s a means of storing existing energy rather than a source of new energy, and inherently less sexy than solarPV.

Hydrogen also has an image problem. There’s no particular reason why the energy that goes into hydrogen production should be ‘green’, and indeed a powerful lobby backs ‘blue’ hydrogen, made by the decomposition of hydrocarbons. Blue hydrogen from ‘carbon capture’ processes looked set to be the dominant source of hydrogen fuel right up to the start of the noughties, leading some alternative energy types to dismiss the nascent hydrogen industry as an oil business front.

But this decade may turn out to belong to ‘green’ hydrogen. With luck we’ll see the emergence of a virtuous circle: surplus power from cheap but unpredictable renewables will be harnessed to giant electrolysers to produce green hydrogen, a clean, high-yield, rapid-fuelling power source for our vehicles and heavy machinery that frees up electricity for heating, air conditioning and control functions… and for making more hydrogen.

Nice outline, as they say.

There are a number of significant obstructions to the hydrogen rollout. For the sake of argument, we can group them under two headers: the ‘fuel cell problem’, and the ‘infrastructure issue’.

Rollout realities

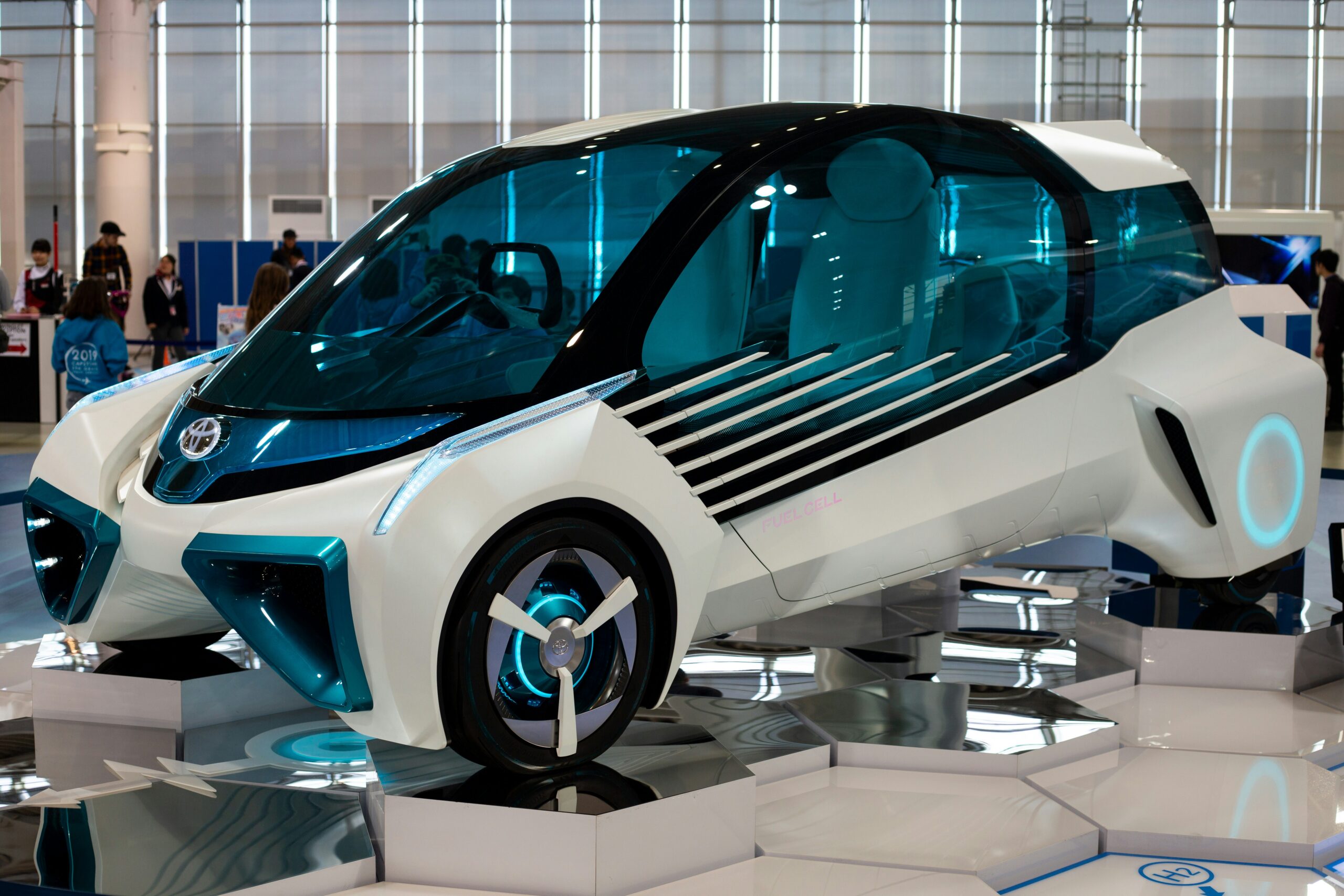

The ‘fuel cell problem’ extends across the practicalities of transport engineering. The headline acknowledges the fact that burning hydrogen isn’t particularly efficient. It’s much smarter to extract the energy via a fuel cell, an small marvel of chemical engineering which enables the gas to give up its energy at low temperature.

Fuel cells are a decades-old technology, but they remain eyewateringly expensive. Most of the 15 or so fuel-cell-equipped car designs listed by Wikipedia are only available on lease from their manufacturers, and all the three exceptions carry US$50,000+ price tags.

Hydrogen vehicle enthusiasts believe that moving fuel cells into the transport mainstream will inevitably bring down prices. They point to the way that high-pressure hydrogen storage, an intractable engineering problem for decades, has been cracked in the past few years by the ready availability of carbon composite tanks. Cheap fuel cells to follow? We shall see.

The ‘infrastructure issue’ is a problem of a different order; a matter of public policy as well as a technical challenge. How is the hydrogen economy to be organized?

Plans like those made by the German and Chilean governments envisage hydrogen being produced by large, quasi-state enterprises, perhaps repurposing the pipelines of the dying natural gas industry. The very largest of them, presently attracting serious attention in EU circles, proposes siting giant electrolysers beside the offshore wind farms and storing the resulting hydrogen in the porous rocks of former oilfields.

At the opposite extreme, initiatives like that announced this year by Australian ‘green fuel’ company Ampol would see hydrogen produced at small local plants, perhaps even at point of sale.

Britain is already storing natural gas in declining oilfields like Humbly Grove on Humberside, and has less potential for on-shore industrial developments than Oz. On the other hand, it has little stomach for large-scale public infrastructure works. The shape of the hydrogen economy is still up for discussion.